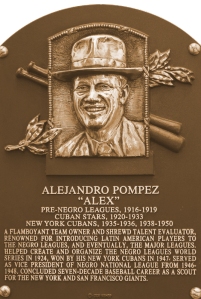

When I was a kid, every Christmas my dad would take me to Barnes & Noble and let me fill a shopping basket with books. When I was about 12, he laid down his first rule: No more baseball! My obsession with baseball history was so total that on my first trip to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown I corrected the Brooklyn Dodgers exhibit, which was missing a pennant. But I had barely heard of Alex Pompez until I read Cuban Star. Colorful, charismatic and a little shady, Pompez was a fixture in Harlem during the 1930s and 1940s as owner of the New York Cubans, a pioneering team of mostly Latin American players that competed in the Negro-leagues. A legend in his time, Pompez was named to the Hall of Fame in 2006, decades after his death, and author Adrian Burgos deserves great credit for preserving his unique contributions to baseball and New York City.

When I was a kid, every Christmas my dad would take me to Barnes & Noble and let me fill a shopping basket with books. When I was about 12, he laid down his first rule: No more baseball! My obsession with baseball history was so total that on my first trip to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown I corrected the Brooklyn Dodgers exhibit, which was missing a pennant. But I had barely heard of Alex Pompez until I read Cuban Star. Colorful, charismatic and a little shady, Pompez was a fixture in Harlem during the 1930s and 1940s as owner of the New York Cubans, a pioneering team of mostly Latin American players that competed in the Negro-leagues. A legend in his time, Pompez was named to the Hall of Fame in 2006, decades after his death, and author Adrian Burgos deserves great credit for preserving his unique contributions to baseball and New York City.

An Afro-Cuban who arrived in Harlem with big dreams and little cash at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, Alejandro Pompez had a classic New Yorker swagger. He quickly got involved in “numbers”, a form of localized gambling that served as both a friendly community lottery and conduit to the criminal underworld in New York’s poorer communities. Burgos takes great pains to explain that the numbers industry was one of the only sources of liquid capital in Harlem (and elsewhere), which is why the community looked past its illegality and baseball teams throughout the Negro-leagues depended on it for financing.

Numbers brought home the bacon, but Pompez’s dreams were in baseball. He soon assembled the New York Cubans, who would compete on and off for the next 25 years, showcasing some of the sport’s best Latin American stars, whether in formal leagues or barnstorming through the country and beyond. One of Pompez’s first big signings, Martin Dihigo, is considered one of the best Cuban players ever. Pompez’s fluency in Spanish, his Cuban heritage and paternal demeanor made him a great recruiter for Cuban ballplayers, though he was not alone in recognizing the island’s talent pool. His cultivation of that talent was pioneering. He was pioneering in his cultivation of that talent, as well as being the first person to seriously scout in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, he even recruited players from Panama and the Bahamas and, pried talent from local fiefdoms, all while staying one step ahead of rivals in the majors and Negro-leagues.

Pompez was also a big player on the local sports scene, securing Dyckman Oval in Washington Heights to serve as the first minority administered baseball stadium in New York City. (Part of the instability of the Negro-leagues was the lack of regular access to a ballpark in the country’s biggest market. The Oval was later turned into the Dyckman Houses, but this site has great photos of the old park. LINK http://myinwood.net/the-dyckman-oval/) The Cubans played host to an exhibition team that included Babe Ruth, and in 1935 made it to the Negro League World Series, where they nearly took out the Pittsburgh Crawfords, perhaps the greatest Negro-league team of all-time.

Things went sour for Pompez when notorious Jewish mobster Dutch Schultz seized control of the Harlem numbers game. Pompez had caught a bad break when a superstitious number won the lottery, leaving him thousands of dollars in the hole, and forced to choose between defaulting on his community or agreeing to work under Schultz to pay off his debts. Despite his painful decision to do the latter, the community never abandoned their support for Pompez, recognizing the white privilege that allowed Schultz to bribe cops and officials, abuse his workers and cheat numbers patrons with impunity once he had forced the local black and Latino numbers operators under his thumb.

Schultz was very much in the cross-hairs of the politically ambitious Thomas Dewey, who was propelled to the New York District Attorney’s seat by slamming Tammany Hall’s relationship with the mob. Once there, he went after Schultz and Pompez, who fled Catch Me If You Can style for more than a year before an international dragnet captured him in Mexico. (My book margins include: “Would make a great movie!”)

Despite a fierce legal battle over extradition, Dewey dragged Pompez back to the U.S. days before the election (an early use of the electoral “October surprise”(LINK http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/October_surprise)), where Schultz was plotting to kill both of them. Unfortunately for Schultz, the Five Families didn’t like the heat that would bring down on the Mafia, and had Schultz whacked before he could pull it off.

At this point you might have forgotten that Pompez was a baseball visionary, if not for the schemes he was cooking up in prison with a Mexican oil magnate who eventually became his rival for Latin American talent when he started the Mexican League. Back in New York, Pompez turned state witness, renounced the numbers game, and turned his focus to baseball.

…

For baseball fans, the second half of the book, post-trial, is a real treat. Pompez is now fully devoted to the New York Cubans and the Negro National League in the final years before it is torn asunder by Jackie Robinson’s major league debut. Robinson’s story is well-trod, but Burgos highlights several interesting tangents. First, dozens of light-skinned Latinos had been playing in the majors since the 1930s, though Robinson still should get credit for breaking “the color barrier,” as dark-skinned and curly-haired Latinos were as barred as blacks before Robinson’s debut in 1947. Second, Robinson’s debut absolutely decimated the Negro-leagues. Even though full integration was years away (the Red Sox didn’t sign a black player for another 12 years), the black and Latino community was enraptured with Robinson and the Dodgers, and turnout at Cubans games plummeted. Finally, contrary to the saintly depiction in last year’s 42, Brooklyn Dodgers General Manager Branch Rickey is depicted ruthlessly pillaging Negro-league teams, ignoring their contracts and stripping their best players without compensation.

Pompez saw the writing on the wall, and parlayed his considerable track record scouting black and Latino players into a position with the New York Giants (who soon moved to San Francisco). During that tenure he oversaw the signing of Willie Mays (one of the best players ever), Willie McCovey (Hall of Fame), Orlando Cepeda (Hall of Fame), Juan Marichal (Hall of Fame), Luis Tiant (229 wins), Felipe and Matty Alou (All-Stars). His protege, Minnie Minoso, ended up on the White Sox as one of the first Afro-Cuban players in the majors.

Pompez was more than just a good scout and salesman –- he personally massaged highly tenuous racial atmospheres during the early years of baseball’s integration, mentoring young minorities thousands of miles from home dealing with hostile managers and widespread Jim Crow laws. Today, more than a quarter of major league baseball players are Latino, including descendants of players Pompez recruited and managed.

I’m not sure we need 256 pages on Alex Pompez. At times Cuban Star slumps through repetition, unnecessary summary, and Negro-league politics that bored both the baseball fan and history fan in me. Perhaps when tackling a figure like Pompez, authors can get to commercial page length by providing contextual chapters rather than doubling down on the primary subject.

For example, we are served gobs of Negro league political drama, but little information on the best teams and players. I would have liked more facts about the other Negro-league teams, especially because the Cubans lost to them season after season, winning the title only once, in 1947. Perhaps discussing the other team owners, Pompez’s peers, would have been interesting. Likewise, Thomas Dewey parachutes in as the co-star for the middle of Cuban Star, but one wouldn’t even realize that he is the “Dewey defeats Truman” from Burgos’s thin character sketch. And while it is true that the banking industry refused to invest in Harlem, and the numbers game was an important part of the community, reading Burgos one could forget that at the height of the Harlem Renaissance the neighborhood had a strong black middle class and international acclaim for its music and literary scene.

Though we now have the state lottery to thank for letting us gamble our savings away and freshly approved casinos to lure suckers in from across the state, the old numbers world reminded me of a different industry – today’s drug trade. Numbers bankers took in bets and disbursed cash after the winning combinations. These bankers employed runners and bag men (as in the drug trade, jobs were separated so no one person could be caught with both gambling slips and cash), as well as lookouts, enforcers, and regional lieutenants. According to the Amsterdam News this industry employed nearly 30,000 Harlemites. A cursory search didn’t yield comparable numbers for the present-day illegal drug market in New York, but if anyone has seen such research, I am curious. I wonder if Richard Wright would have spoken of today’s drug kingpins as he did the numbers kings of old: “They would have been steel tycoons, Wall Street brokers, auto moguls if they had been white.”

Minor criticisms aside, Burgos has documented an essential chapter of New York and baseball history. One would hope that someone with Pompez’s history as a Negro-league innovator and bridge to Latin American baseball would have a safe legacy. But when his name was brought up for Hall of Fame induction many years after his death, Keith Olbermann was among those leading the charge that a “former racketeer” had no place in Cooperstown.

In some respects, this entire book is framed as a specific response to Olbermann and other critics, as Burgos was on the very committee that pushed for Pompez’s inclusion. This realization gave me pause, and explained the generally positive depiction of the numbers game. Such flattering accounts of subjects are far more common in sports biographies than serious histories, and Burgos is straddling the two genres here. But given what even casual baseball fans already know about the Negro-leagues, scouting and the importance of Latin American players in today’s game, Pompez comes across as a worthy Hall of Famer, even when discounting for possible Burgos bias.

Pompez is likewise is a hall of fame New Yorker. The unknown quasi-immigrant from Cuban Florida came here to make it big, and he did. He reinvented himself several times, first as numbers hustler, then as a local sports magnate, and finally as baseball’s ambassador to Latin America. He crossed paths with iconic New Yorkers like Babe Ruth, Dutch Schultz, and Thomas Dewey along the way while living the good life during the Harlem Renaissance. He instilled pride uptown, giving black and brown New York a baseball team and even a baseball stadium of their own. Perhaps most profoundly, Pompez understood the injustice of racism, counseling a fierce mix of patience and vigilance in pushing for baseball integration, which paved the way for the rest of society. As far as I know, there is no tribute to Pompez anywhere in the City.

Sixth Avenue between 110th and 116th Street used to be called Pompez Boulevard at the peak of the Cubans’ heyday. Today it is co-named Malcolm X Boulevard for the man who shook racial politics nationally from his Harlem base several decades later, and Lenox Avenue, for philanthropist James Lenox. Lenox’s projects included major funding for the Presbyterian Hospital, where the Columbia Medical Center is located, and contributing his massive rare books collection to the City, helping found the New York Public Library. That’s some avenue!

Reading about our city’s racial history is hard, and it certainly isn’t always fun. By bringing the charismatic Alex Pompez to life, Adrian Burgos offers us a chance to thoughtfully stroll the last days of segregated baseball in New York City with one of its most important innovators as our guide.

…

Cuban Star was published by Hill & Wang (2011).